How we deploy new features at iAdvize

This post was originally published on Medium.

Photo by ian dooley on Unsplash

New features are unsurprisingly important for iAdvize. Our business relies on the tech team’s ability to develop and implement new features in as short a time as possible. Those will however be challenging, create bugs and they will need to integrate within a sometimes perilous existing code base. They definitely make business sense, but they are technically dangerous.

Business of course prevails, but not a the cost of bad quality software, either external or internal. Let’s talk about how, as a tech team, we have evolved our strategy to ship new features to production and how we now use feature flags to meet those demands.

What we don’t want to do anymore

We don’t want to ship a new feature for 100% of our users at once. We want to test it and iterate first, internally and with beta testers.

We don’t want to deploy huge refactors at once. It’s sometimes tempting to rewrite a significant part of an application, even if it’s only tangentially related to the new feature itself. This approach usually leads to several months of back-and-forth and ends up with an enormous pull request where the new feature is drowning in old code being rewritten. No one can (or wants to) review that.

If something goes bad after deployment (and it will), we’ll rollback and try to fix bugs, adding to an already sizeable amount of code and potentially freezing deployments in the meantime.

We don’t want to implement special client code. It’s easy to implement new things for one client in particular in order to make a deal happen. While this sounds like a nice quick-win, it’s not. Product Managers and Customer Angels can’t onboard a client to this new feature without a developer deploying a change to production.

Furthermore this special if (clientId = ‘1345678’) { … } will make our code

hard to maintain over time: it creates a corner-case that will become harder to

understand and justify while holding up a part of our application’s logic

hostage to a single hardcoded clientId.

We don’t want to maintain and drag feature-branches. The new feature we’re building may be one in many simultaneous tasks at hand on a single code base. Isolating its code in a feature-branch may be traditional and provide a commit-by-commit history of the changes, but we do not want to risk either the throes of updating the branch with the rapidly moving master branch or simply finding out late in the game that two teams ended up refactoring the same shared helper for example. Committing often, pushing often, merging often: those are good clean guidelines to live by.

What we do now: feature flags

Wikipedia says “a feature flag […] is a technique in software development that attempts to provide an alternative to maintaining multiple source-code branches (known as feature branches), such that a feature can be tested even before it is completed and ready for release. Feature toggle is used to hide, enable or disable the feature during run time. For example, during the development process, a developer can enable the feature for testing and disable it for other users.”

Using a feature flag in the code resembles implementing special client code. It looks like this in pseudo-code:

if flag “new user profile” is activated for the logged-in user

then show the new user profile

else show the old user profile

There’s no magic here, “it’s just an if”©. The key difference with our previous clientId example however is that we’re not setting that clientId as a prerequisite in the cold marble of our code: we’ve left this flag’s activation up for something else to manage.

The pivotal part is indeed evaluating the value of a flag for the current user, and for this we use Launchdarkly. It’s a SaaS tool where you first create flags in a clean UI and then request the evaluation of this flag for a user within the API or SDKs. Our product managers have access to Launchdarkly and can pilot the deployment of a feature themselves, targeting very specific users via their email address, client IDs or whatever but also through some of LaunchDarkly’s nice “bulk” features such as the Percentage Rollout.

Let’s say a “user” is shaped like this…

user = {

id: '12345678',

email: 'user@iadvize.com',

companyId: '1'

lang: 'fr',

}

…and that we need to test out a new form factor for our user profiles in-app.

We can create rules in Launchdarkly for the newly created “new-user-profile” flag:

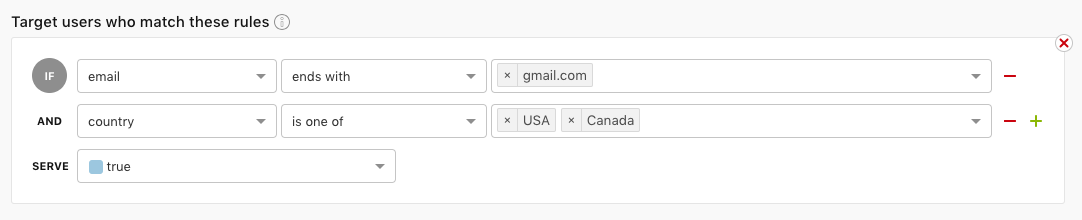

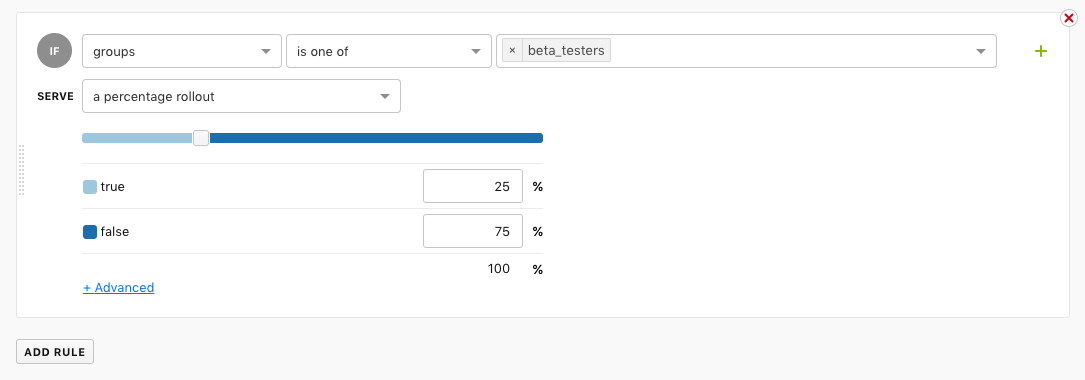

if userId is ‘12345678’, flag value is true, else false. This will activate the new user profile UI for this specific user.if email contains “iadvize.com", flag value is true, else false. This will activate the new user profile UI for all iAdvize employees. Useful to test things internally.if companyId is 1 or 1234 or 34, flag value is true, else false. This will activate the new user profile UI for the beta testers companies 1, 1234 and 34.if lang is “en", flag value is true, else false. This will activate the new user profile UI for english-speakers. for 20% of users, flag value is true, else false. This will activate the new profile for 20% of the user base, allowing us to deploy progressively.

Two Launchdarkly rules (basic and percentage rollout) from the docs

With such a wide array of options, it may be tempting to think of LaunchDarkly as a part of our product, a separate tool used to build the modularity of our features (and therefore pricing options) around its flags. We have however opted to cleanly separate the production and development concerns of feature flipping. LaunchDarkly is a temporary tool we use to smooth our development process and potentially challenge tentative features, but core, long-term and configurable feature-sets cannot rely on external SaaS code.

The new strategy: how do we deploy a new feature with a feature flag

With the introduction of feature flags (from Launchdarkly or not, which service you use is ultimately just an implementation detail), our strategy of developing and shipping new features changed and can be summarized in a small list of steps.

1. Identify and isolate the old code.

To identify the old code, we ask ourselves this question: what will be gone once the new feature is shipped and what will be used by those unaffected by the flag?

When then try to isolate that bit as much as we can. We don’t hesitate to rewrite some of the code to make this part accessible via one unique point / API but it’s not the main mission and shouldn’t be the core of what we do. This isn’t a refacto.

Maybe there’s no old code and you’re creating a feature from scratch. That’s great, nothing to do then!

2. Add a feature flag and wrap the code

We create the feature feature flag on Launchdarkly. We usually also create a helper function to test its value for the current user in the app we’re working on, that is to say a function that abstract the logic of collecting the user informations, build the user payload object, send it to Launchdarkly to evaluate the flag and return the evaluation result.

We then wrap the call to the old code : if the flag is evaluated to false (or to the value corresponding to the old code), we call the old code.

If the flag is evaluated to the value corresponding to the new feature, we will eventually call the new code but it’s probably just a function call that does nothing for now.

At this point we’ve established our “default”: if not given any other instructions from our flag manager, the legacy code will be executed. We’ve kept the status quo from our users’ perspective but we’ve made a new launching ground for us to develop from.

3. Develop atomically, push to production early

We then write the new code peacefully in small chunks. Pull requests are easily reviewable.

Because the flag is off for everyone except the dev team, we merge to master and deploy to production as soon as possible. This way we can detect small bugs early.

The new code “bubbles” to production, even if it’s not used yet. It’s usually better to push small commits to production than big ones: bugs will be less impacting and easier to identify. We can then test on production data very early on.

4. Deployment to all users

Once the development and the final QA are done the flag is activated for some users, usually internally first then live beta users rapidly after. The team gets feedback and iterates on the new feature.

When the feature fits the targeted group’s feedback, the team progressively activates the flag to 100% of the user base. We keep an eye on production errors with a tool like Sentry. If something goes wrong, we simply switch off the flag. The bug can be fixed with no excessive stress: users are not affected anymore because they are back on the old code, there is no deploy freeze and no commit revert. Once the fix is merged, we deploy and repeat the process.

5. Cleaning

After a few weeks, the team removes the if from step 2 alongside the helper function and legacy code, which we had neatly isolated. We deploy once more and usually wait a few days to delete the flag on LaunchDarkly, always wary of a potential rollback. The flag is now gone from our code, gone from LaunchDarkly: the job is done!

Some real-life examples

We need to change some HTTP calls a backend PHP service makes.

Imagine that a backend service makes HTTP calls to the Twitter API V1 and needs to switch on Twitter API V2.

First, we isolate the calls. We refactor things a little to have one simple twitterService.old.php file with a clean API.

We create a twitterService.php. It has the new API (probably the same as the old service), but all functions are empty.

We create the new flag on Launchdarkly and the helper function used to test its value for the current user. Everywhere a call to the twitterService.old.php API is used, we wrap the call to use either the new or the old service.

if (newServiceFlag(user)) {

$oldTwitterService->makeCall();

} else {

$twitterService->makeCall();

}

We push to production like this, with the flag switched off for everyone except the dev team. Building from this base, the team develops and pushes atomically. Once the refactor is done, they switches the flag progressively. Everything’s ok after a few weeks ? The team removes the use of twitterService.old.php and the old code.

We need to rewrite a Redux workflow

Imagine a Redux workflow done with multiple middlewares, hard to maintain and hard to extend. We need to add a new feature and decided to use Redux-Saga to rewrite the workflow, with the new feature inside.

First, the team will isolate Redux actions that are part of the old workflow. It will maybe change code a little to be sure one single action starts the workflow. To easily distinguish the actions, the team will probably suffix the action types with a distinct label like MY_ACTION_TYPE_OLD.

The team then once again creates the flag. Everywhere the old starting action is dispatched, it gets wrapped in a call to the helper function.

if (newWorkflowFlagActivated(user)) {

store.dispatch(newAction());

} else {

store.dispatch(oldAction());

}

Once the new workflow shipped, they switch the flag progressively. After a few weeks, the old actions and middleware are safely removed.

We need to add a UI

Let’s say we need to add a user profile in our app.

We identify and isolate the old code. But there is none! This is a completely new UI. We create a UserProfile component that render nothing and the Launchdarkly flag.

Instead of rendering UserProfile directly, you guessed it, we check the helper function.

// somewhere in the JSX parent component

// ...

{ userProfileFlagActivated(user) && <UserProfile />}

// ...

Then, we develop the UserProfile component. When everything is ready and shipped to production, the flag will be switched on progressively in order to make the new UserProfile accessible to everyone. After a few weeks, the userProfileFlagActivated(user) check will be removed.

Conclusion

The development and deployment process based on feature flags we now use in the iAdvize tech team works in five steps:

- Isolate and identify the old code, if there is any

- Create the flag and wrap the code around its evaluated value

- Develop atomically and push to production early

- Onboard all users progressively

- Wait and clean the old code

We see a lot of advantages in doing so. We easily iterate with beta testers before opening a new feature to everyone. We also deploy more often while having less critical bugs and less deployment freezes because we no longer merge huge pull requests. We ship new, better-tested features faster.

We also have taken back control on old legacy apps that were nearly abandoned. We have the tool to consolidate them and add new features despite their difficult code base.

When should one use this workflow? As we illustrated with the examples above, using a feature flag works well for new features or refactors, big or small. The implicit rule of thumbs we tend to use is: use a flag unless it takes longer to set up than to actually do the job. A bugfix doesn’t require a flag but for almost everything else and especially very risky lines of code, it’s a good and secure habit to develop.

A big thanks ❤️ to all my iAdvize colleagues that helped me write this post: Fhenon De Urioste, Fred Arnoux, Wandrille Verlut and Benoit Rajalu!