State and Store in frontend codebases

This post was originally published on Medium.

Taking the time to separate the State, the Store and the Workflow in frontend codebase.

For the last two years my team has been continuously refactoring a large legacy app. We learnt a lot of things in the process but one of the most important tools we found was having a new outlook on two core front-end concepts: the State and the Store.

It turned out that cutting problems into State, Store and — as we will see — Workflow “bits” really helped us deliver a better architecture, maintain the codebase in the long term and choose the right libraries to build upon.

Let us show you why. We will take you through the same journey we did, first by looking at the state management libraries we sometimes blindly use. Then we’ll deconstruct the core concepts and highlight how asking the right questions about them lead to demonstrable benefits.

State management libraries

There are a lot of “state management” libraries built for frontend codebases. We inherited Redux and tried to stick with it at first, but it soon became apparent it was not helping us get the job done.

A common Redux situation

Imagine an app dealing with users.

There are some actions creators, for example:

export const fetchUsers = () => ({

type: "FETCH_USERS"

});

export const fetchUsersFailed = () => ({

type: "FETCH_USERS_FAILED"

});

export const fetchUsersSucceeded = (users) => ({

type: "FETCH_USERS_SUCCEEDED",

payload: {

users

}

});

export const createUser = (firstName, lastName, picture) => ({

type: "CREATE_USER",

payload: {

id: Math.round(Math.random() * 1000000),

firstName,

lastName,

picture

}

});

export const createUserFailed = () => ({ type: "CREATE_USER_FAILED" });

export const createUserSucceeded = (payload) => ({

type: "CREATE_USER_SUCCEEDED",

payload: { user: payload }

});

We have to handle some actions in a reducer.

const initialState = { loading: true, users: [], error: undefined };

export function reducer(state = initialState, action) {

console.log({ type: action.type, action });

switch (action.type) {

case "FETCH_USERS_SUCCEEDED":

return {

...state,

loading: false,

users: action.payload.users.filter(

(apiUser) => apiUser.type !== "ADMIN"

)

};

case "FETCH_USERS_FAILED":

return {

...state,

loading: false,

error: new Error("oops")

};

case "CREATE_USER_SUCCEEDED":

return {

...state,

users: [...state.users, action.payload.user]

};

case "CREATE_USER_FAILED":

return {

...state,

error: new Error("oops")

};

default: {

return state;

}

}

}

Then in a middleware or two.

import { fetchUsers, createUser } from "./fake-fetch";

import {

fetchUsersSucceeded,

fetchUsersFailed,

createUserFailed,

createUserSucceeded

} from "./actionCreators";

export const middleware = ({ dispatch, getState }) => (next) => (action) => {

next(action);

switch (action.type) {

case "FETCH_USERS": {

fetchUsers()

.then((payload) => {

dispatch(fetchUsersSucceeded(payload));

})

.catch(() => {

dispatch(fetchUsersFailed());

});

break;

}

case "CREATE_USER": {

const currentUsers = getState().users;

if (currentUsers.length >= 10) {

dispatch(createUserFailed());

}

createUser()

.then((payload) => {

dispatch(createUserSucceeded(payload));

})

.catch(() => {

dispatch(createUserFailed());

});

break;

}

default: {

}

}

};

We need at least a selector:

export const getUsers = (state) =>

state.users.map((user) => ({

...user,

picture: user.picture || "https://i.pravatar.cc/300 "

}));

And a view:

import React from "react";

import { useDispatch, useSelector } from "react-redux";

import { getUsers } from "./selectors";

import { createUser } from "./actionCreators";

import Users from "./components/Users";

import UserForm from "./components/UserForm";

export default function App() {

const dispatch = useDispatch();

const users = useSelector(getUsers);

console.log({ users });

const handleFormSubmission = ({ firstName, lastName, picture }) => {

if (firstName && lastName) {

dispatch(createUser(firstName, lastName, picture));

}

};

return (

<>

<Users users={users} />

<UserForm onSubmit={handleFormSubmission} />

</>

);

}

You can find a full Codesandbox for this code.

This is an illustration of Redux cruft. It’s not a secret that people complain about Redux and other Flux-inspired libraries boilerplate. There are lots of files (action creators, reducers, middlewares, selectors), especially when we use combineReducers. It is hard to maintain in the long run from a strictly technical point of view.

It also comes with a strong paradigm based on user events called “actions”. What if it does not fit the way you think of your app? In our case, the vast majority of the actions were in fact tied to a single handler (reducer or middleware). Why not use a simple function instead?

The danger of using Redux by default in this situation is implementing things that don’t fit our needs.

On top of this, the fundamental issue for us was how hard it became to see the big picture of what we were implementing. Our business rules were spread out in the codebase. They were hard to centralize because of what Redux needs in order to work.

In the example above, some rules are implemented in the view (a user must have both firstName and lastName), some in the action creator (the new user ID is a random 10 digit number), some in middlewares (you cannot create more than 10 users) or in selectors (users lacking an avatar get a random one). The process of creating a user is spread out. There is no single file that handles the whole thing from the form submit event to the saving of the new user in the Store after receiving the backend payload. In a regular Redux app, the process is at least always separated between synchronous storage (in the reducer) and asynchronous logic (in the middleware).

We used combinedReducers a lot to split the codebase in smaller units. But we were unable to design the state the way we wanted. With combinedReducers, we can’t say for instance that the State for our early example is ’loading’ | ‘failure’ | { users: NonEmptyArray<Users>, ... } in order to prevent impossible states (here having an empty user list, for example).

Does it mean Redux is a bad library? Not at all. But it shows that we can use a library for the wrong reasons, when its model does not match the knowledge we have of the business problem. Realizing that while being up to our necks in cruft meant we had to pause to understand the situation better.

Understanding the compromises we make when choosing a state management library

We started looking at other tools. It helped us work out typical patterns and understand what are the principles of all “state management” libraries.

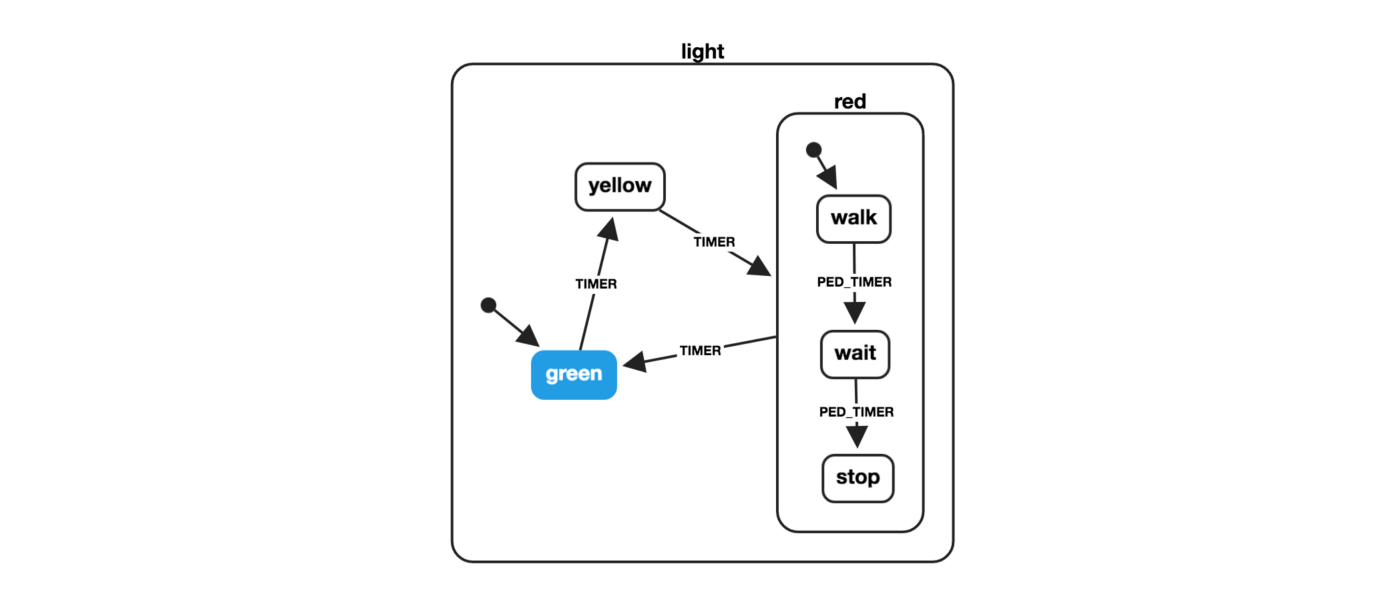

Some of them have something to say about the shape of our State and its surface API. Redux for example makes us write actions that can be seen as a finite API on our State. It’s better than allowing every part of the codebase to update the State in every way possible, without a consistent set of business rules. We like the idea, if not the execution as we’ve discussed. In XState, a state machine library, the State should be designed with a state diagram in mind. This also helps us secure what is possible and what is not. We like that too!

However the constraints libraries can sometimes impose on the State are more technical. We saw that Redux will make us split our code across multiple files. Redux’s combineReducers or Recoil’s way of combining atoms, for example, also have the tendency to shape the state as an object. All of this prevents us from centralizing business logic and modeling the state more finely.

Some libraries and tools force us to use their store in a specific context, like React’s useState and Recoil: they are for React views only. That’s a strong constraint. What if we need the store in a vanilla view? What if we follow an architecture where the view is a simple projection of the state and the workflows of the app lies elsewhere? This was our case.

What do we also love or hate about “state management” libraries? Asynchronous paradigms! Communicating Sequential Processes (CSP), like in redux-saga, streams found in RxJS or redux-observable, simple promises returned in Recoil selectors, and so on and so on.

But are they related to the problems of defining our state or storing it in some place? They should not be. They are workflow issues. If a library enforces strong limitations on its Store or State concepts to favor its Workflow, are we sure we will be able to design the States we really need?

Some libraries do let us completely decide the shape of our State. That’s the case of React’s useState hook and other “small” store libraries that follow the Unix “Do one thing and do it well” philosophy. We like that! They usually also let the user choose the workflows they want. We also like that.

Finally, tools like Relay or Apollo help us write apps that are “projection”, when we have to connect to an API to retrieve data and present it in a UI without complex workflows. They separate concerns really well: there is the backend state described by the API payload / GraphQL schema on one hand, and the store that is handled completely by the library (with cache, optimizations, etc.) on the other hand. It even lets us have local states in our views when needed.

It is however less relevant to use a library like this when our app is more about “composition” (of workflows, datasources, or complex functionalities) than “projection”.

Evidently not all “state management” libraries say the same thing about our dilemma: some are really minimal, others come with strong paradigms and opinionated workflow management. They all somehow have something to say on either what the state should look like, what workflow tool or what views you should use. We therefore have to be carefull: what type of contract are we getting into?

What became clear for us is that we should not have to shape the all-important State simply because the Workflow or the Store comes with baggage.

What is a Store? What is a State?

Why should we be so defensive of our State? Most frontend applications manage some data (the State) that is stored somewhere (the Store) and provide their users with functionalities to tie them all together (the Workflow).

We can be unaware of these concepts and the specific way we compose them in order to build our apps. They are too easy to overlook.

Wikipedia’s general definition of a “store” is “a place where items may be accumulated or routinely kept”. Like in “this building used to be a store for old tires”. In computing, it’s a direct synonym of “memory”.

A program stores data in variables, which represent storage locations in the computer’s memory. The contents of these memory locations, at any given point in the program’s execution, is called the program’s state.

The store is the memory. The state is what we put in the memory.

A cat (the state) in a box (the store).

He’s not so happy because a state always prefers to live in the world of states, away from all real world problems. Like all cats.

From Unsplash, by Sahand Babali

The content/container relationship between these two things is basic, but worth keeping in mind. It raises new questions.

In real life we choose the container based on the content. Let’s say the content is liquid. Would you store it in a paper bag? No, because the characteristics of the content implies we choose a corresponding container. I would go for a bottle.

How about software? The relationship is the same and yet we don’t seem to approach the problem this way with many of the “state management” libraries available. The State has a shape, and it is up to us to make sure the Store adapts.

What is a workflow then? It is neither directly the state nor the store in “state management” libraries. It is where we find the concepts of stream, middlewares and asynchronous stuff. Workflow is about coordinating things and managing effects on the outside world.

Combining the Store, State and Workflow in our apps

Armed with these three different concepts in mind, let’s try to see how we can refactor our initial example. What will help us is identify the questions we ask when we think about State and Store.

At the end of the process, we will have a codebase that groups things that look the same, and separate things that look different. Everything that is about the state will band together, separated from store and workflow issues.

Content and container as code

When we think about the state of our app, we go down a very specific line of questioning. They all aim at turning practical issues into models of a solution:

- What does the data represent?

- What entities do I need to model the problem at hand?

- What state diagram can I draw?

Defining this model in code leads us to write the state definition and the surface API for it. The functions would have specific signatures. Let’s say the application state is defined as AppState.

To “read” the State, we would write AppState -> Substate functions (given the State, we extract something from it). They are State accessors .

To “update” the State we would write AppState -> AppState (modifying the state, emptying an array, for example) or A -> AppState -> AppState (using something to modify the state, like adding something in the previous one to get a new one).

This is the world of ideas. We’re using pure functions. It’s all theory. It is the liquid of the real-life example.

Defining the store leads to a totally new set of questions:

- Where do we store the data?

- How do we read it?

- How do we write into the store?

- How do we subscribe to its changes?

To “read” from the store, the signature looks like () -> AppState. It simply returns the state from “somewhere”.

To “update” something in the store, we have AppState -> () -> void or (AppState -> AppState) -> () -> void functions (give something a new state or a modifier function and apply the change).

We will also want to “listen” for change by giving the store a function it has to call back when the content changes, for example, (() -> void) -> void.

Those of you familiar with functional programming will have recognized the IO signature () -> X explicitly used here to point out that these functions are effects and not simple ideas anymore. Yup, this is the real world. And it’s a container that can accept any content we have: it is a magic bottle.

Rewriting the Redux situation

So let’s write a new version of the user app from the beginning by sticking to a strict State / Store separation. We will write the state first to encapsulate business rules, then will come the store and the workflow, and finally, the view.

We define the state by writing pure functions. Thinking of a succession of states we transition to according to specific business rules really helps. Code like this is easy to read, easy to test and easy to maintain.

Here we want to highlight the app could be loading, in error, or loaded with a non-empty list of users. When the app is loaded, it contains a list of Users.

// state/index.ts

import * as NonEmptyArray from "fp-ts/lib/NonEmptyArray";

import * as User from "./user";

export type State = Loading | Failure | Loaded;

export const initialState: Loading = "Loading";

type Loading = "Loading";

type Failure = Error;

type Loaded = { users: NonEmptyArray.NonEmptyArray<User.User> };

// state/user.ts

export type User = {

id: string;

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

picture?: string;

};

That is the shape of our state! We will write an API to manipulate it. We don’t want to access data directly but with functions: this lets us add business rules as code, if needed, and it will make it easier to refactor internal entities in the future. Having one level of indirection can always be helpful: our future selves can change the shape of a User completely without changing its API.

// state/index.ts

export const decode = (apiPayload: unknown): Loaded | Failure => {

// parse payload

// remove admins

// if something goes wrong, return Failure

};

export const users = (state: Loaded) => state.users;

export const addUser = (user: User.User) => (

state: Loaded

): Loaded | Failure => {

if (state.users.length >= 10) {

return new Error("oops");

}

return {

...state,

users: [...state.users, user]

};

};

export const isLoading = (state: State): state is Loading => // ...

export const isError = (state: State): state is Failure => // ...

export const canCreateUser = (state: State): boolean => //...

// state/user.ts

const DEFAULT_USER_PICTURE = "https://i.pravatar.cc/300";

export const id = (user: User): string => user.id;

export const displayName = (user: User): string =>

`${user.firstName} ${user.lastName}`;

export const pictureOrDefault = (user: User): string =>

user.picture || DEFAULT_USER_PICTURE;

export const createNew = ({

firstName,

lastName,

picture

}: {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

picture?: string;

}): User => {

const id = `${Math.round(Math.random() * 1000000)}`;

return {

id,

firstName,

lastName,

picture

};

};

There it is. We now have our state and the API to manipulate it. It centralizes the few business rules we have: how should firstName and lastName be combined, what is the default user picture, what is a new user id, the 10 users limit, no admins in list. No more leaking of the business logic through various files.

Now that the state is defined we will delegate the concern of storing it to a library.

At iAdvize, we ended up creating @iadvize-oss/store, a minimal store library. This is our magic box: completely agnostic of the state and the context it will be used in (not only in React views). We also strived to make it as compatible with functional programming as we could. Let’s use it here.

// store.ts

import * as Store from "@iadvize-oss/store";

import * as State from "./state";

export const store = Store.create<State.State>(() => State.initialState)();

We will probably also need two small services (our only “workflow” part) that will coordinate asynchronous requests with storage.

// service.ts

import * as User from "./state/user";

import * as State from "./state";

import { store } from "./store";

export const createUserAndSave = ({

firstName,

lastName,

picture

}: {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

picture?: string;

}) => {

const currentState = store.read();

if (!State.canCreateUser(currentState)) {

return;

}

const user = User.createNew({ firstName, lastName, picture });

fetch(...)

.then(() => {

store.apply((currentState) => {

if (State.isLoading(currentState) || State.isError(currentState)) {

return currentState;

}

return State.addUser(user)(currentState);

})();

})

.catch((error) => {

store.apply(() => error)();

});

};

export const init = () => {

fetch(...)

.then((payload) => {

store.apply(() => State.decode(payload))();

console.log({ state: store.read() });

})

.catch((error) => {

store.apply(() => error)();

});

};

The view has now two simple responsibilities: being connected to the store with a special hook that reads the current state and subscribes to the store to listen for future updates (ie. being a reactive view) and handling new user form submissions by calling the corresponding service. Not less, not more.

// App.tsx

import * as React from "react";

import { useState } from "@iadvize-oss/store-react";

import * as State from "./state";

import { store } from "./store";

import { createUserAndSave } from "./service";

import Users from "./components/Users";

import UserForm from "./components/UserForm";

const handleFormSubmission = createUserAndSave;

export default function App() {

const state = useState(store);

if (State.isLoading(state)) {

return <>Loading...</>;

}

if (State.isError(state)) {

return <>Something went wrong</>;

}

return (

<>

<Users users={State.users(state)} />

<UserForm onSubmit={handleFormSubmission} />

</>

);

}

Finally, the root of the app will be responsible for calling init service after mounting the views.

import * as React from "react";

import { render } from "react-dom";

import App from "./App";

import { init } from "./service";

const rootElement = document.getElementById("root");

render(<App />, rootElement);

init();

Here is the full Codesandbox example.

What have we done in this example? We have defined the state and its API isolated from the rest of the codebase (in the state/ directory). We then set up a store for it and two services. With that ready, we added a view with the simple responsibility of subscribing to the store, reading it and returning the corresponding UI. When an action occurs on the interface, the view just has to call the corresponding service. This looks a lot like Flux, doesn’t it?

Business rules are clearly grouped in the definition of our state. Storage issues are completely out of sight in the store created with @iadvize-oss/store. No real workflow paradigms are in place here but we could introduce powerful libraries (Rx, CSP, etc) to coordinate things like we did with our “services”.

State, Store and Workflow, clearly separated.

Remember, the store is just a box. If the business dictates the state is liquid, the store adapts and becomes a bottle. Not the other way around. The state is where the hard business questions must be answered. This is the real knowledge of the app and one of the most important missions of software developers.

Software design is about constructing models, which is an exercise in knowledge representation. It is about seeking Truth and writing it down. That is the #1 priority.

Anything about software design that prioritizes "maintainability" is putting the cart before the horse.

Eric Normand (@ericnormand)

We ended-up doing just that to our legacy app.

For the State we leverage Typescript and the typing libraries we already used to model states with state diagrams and opaque types in mind.

For the Store we use multiple instances of @iadvize-oss/store’s store for different states.

For the Workflow, we postponed the discussion a bit. We still rely on redux-saga and its CSP paradigm when we need to coordinate complex workflows even if we don’t put anything in the Redux store. It is strange but it works very well. We also use Task from fp-ts to write new services. If someday we want to use the concept of streams for a new feature we will look at RxJS without having to rethink the whole app.

Design is separating things into things that can be composed

In his “Design, Composition and Performance” talk, Rich Hickey shared the controversial idea that Design is first about separating things. We might think design is only about combining stuff but, he says, we first have to deconstruct the problem. We have to cut it in smaller problems until we have “solutions” that are about “one or a few things” (Unix philosophy) that can be composed gracefully to solve the initial problem.

By cutting the problem into State, Store and Workflow problems (and other things, probably) we can focus on each of them separately and combine them the right way for the specific app we have to build. It scales very well because it doesn’t mix different things together or force a specific tool.

We don’t always need to go that far. We can sometimes agree to the specific contract of a “state management” State + Store + Workflow combo and choose a library that matches our initial needs well enough. It is especially time-saving for small or “quick-and-dirty” apps.

But be aware! We sometimes use libraries that are said “scalable” but are only so if they match the way you model the knowledge of the business. If you have to arrange the code in a way that muddles the clarity of your business rules because of technical constraints, it becomes hard to maintain and hard to share with others. A good codebase that scales well lets us add a new tool for part of the workflow when it’s relevant, a new entity in the state when it’s needed.

It’s therefore always helpful to remember the concepts hidden behind our choices. That’s what we tried to do in my last project and what you can do too. Lots of benefits resulted from this.

Isolating the states challenged the app’s architecture for the better, helping the codebase describe more of the business knowledge.

Looking at new libraries with the three concepts in mind made us more careful when adding one: does it impose something on our state? What are the impacts for the storage? How can we connect it with the existing workflow tools?

Finally, separating State, Store and Workflow helped us achieve a better separation of concern and better maintainability down the line. With the right concepts clear for all to see, it was also easier to communicate and work together on the same codebase.

Having taken the time to think from first principles, the State, the Store and the Workflow, really pays off in the middle and long term. We can only encourage you to do the same.

A huge thank you to my frontend colleagues for their time and help in writing this article, especially Wandrille Verlut, Nicolas Baptiste, Nicolas Maligne and of course Benoit Rajalu without whom it would not have been possible to make sense of my first drafts ❤️