On "A Philosophy of Software Design" by John Ousterhout

John Ousterhout is an awarded American professor of Computer Science. Born in 1954, his career follows the one of those that have been part of the beginning of Computer Science in the US: prestigious universities, fundamental Computer Science work, big companies and a bit of entrepreneurship.

In 2018 Ousterhout publishes “A Philosophy of Software Design”. I’ve read the book last summer and found it very interesting, specially in how it can help us do Software at BlaBlaCar.

Software Design

Without any surprise, “A Philosophy of Software Design” is about Software Design, ie. the macro view one should take to architecture or design programs: looking at the problem and decomposing it into independent smaller pieces. For us at BlaBlaCar: what are the user features we have to support, and how should they be architectured.

So the book is not about Software Development (ie. programing languages, for loops, objects and classes, inheritance, etc.), nor Software methodologies (ie. Agile, versioning, design patterns, etc.), although they are of course all linked.

This focus on Software Design is fundamentally important. As a discipline, it’s not present that much in the day to day work of Software Engineers. That’s very paradoxal given how much leverage investing in good Software Designs can have - we’re talking in order-of-magnitude improvements here. That’s where we should invest more of our time.

We won’t try to sum up the book in its entirety here. You can read the book’s table of content for that: it gives a pretty strong overview of the book already, and enough food for thought to start designing software better. Let’s focus on some key points that I’ve found relevant for us instead.

Complexity

Software Design is all about managing Complexity, and this should be the start of all software initiatives. Ousterhout defines complexity in a pragmatic way, “anything related to the structure of a software system that makes it hard to understand and modify”, and proposes that we reason with a cost/benefit ratio.

When a codebase is complex, it costs a lot to do even a small change with low benefit. When an architecture is simple, it costs little to implement a significant change that has a high benefit.

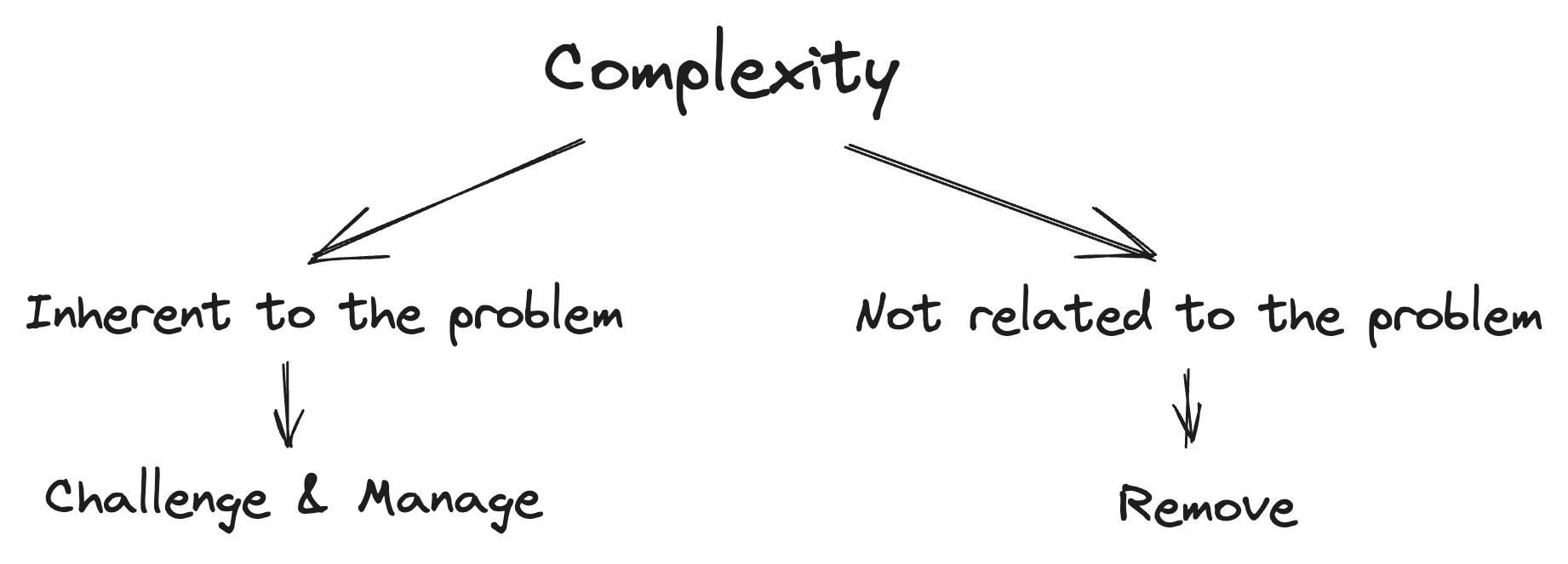

We have two kinds of Complexities to deal with. The first is inherent to the problem solved. 2FA login for example is an intrinsically complex feature. This should be challenged and managed. The second kind of Complexity does not relates to the problem solved. Add the Redux library in a legacy web codebase and the code is immediately harder to grasp. This Complexity should be removed.

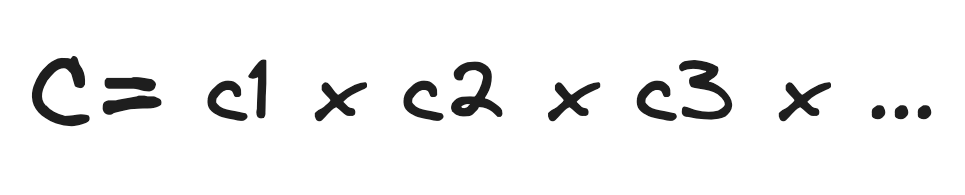

The issue with Complexity is that it’s incremental. It compounds over space (the codebase) and time. A bit of Complexity somewhere is not a critical issue but multiple complex parts there and there can make the global structure extremely challenging overnight.

Consider Complexity as a factor to be multiplied and not merely added.

Managing Complexity

Our job as Software Engineers, or Software Designers we should say, is to understand a given problem and manage its inherent Complexity the best we can, and in doing so, remove any unnecessary Complexity. How to do that?

First, we should not introduce unnecessary Complexity. The book details a lot of good postures to follow that I will rephrase and illustrate like so: be obvious with the code (eg. via the names you choose for variables, methods, etc.), be consistent in the codebase (eg. use an uniform code style, document conventions and patterns, choose a few Boring Technologies and use them extensively), use comments (they should be written close to the code and provide high-level clues) and make impossible states impossible.

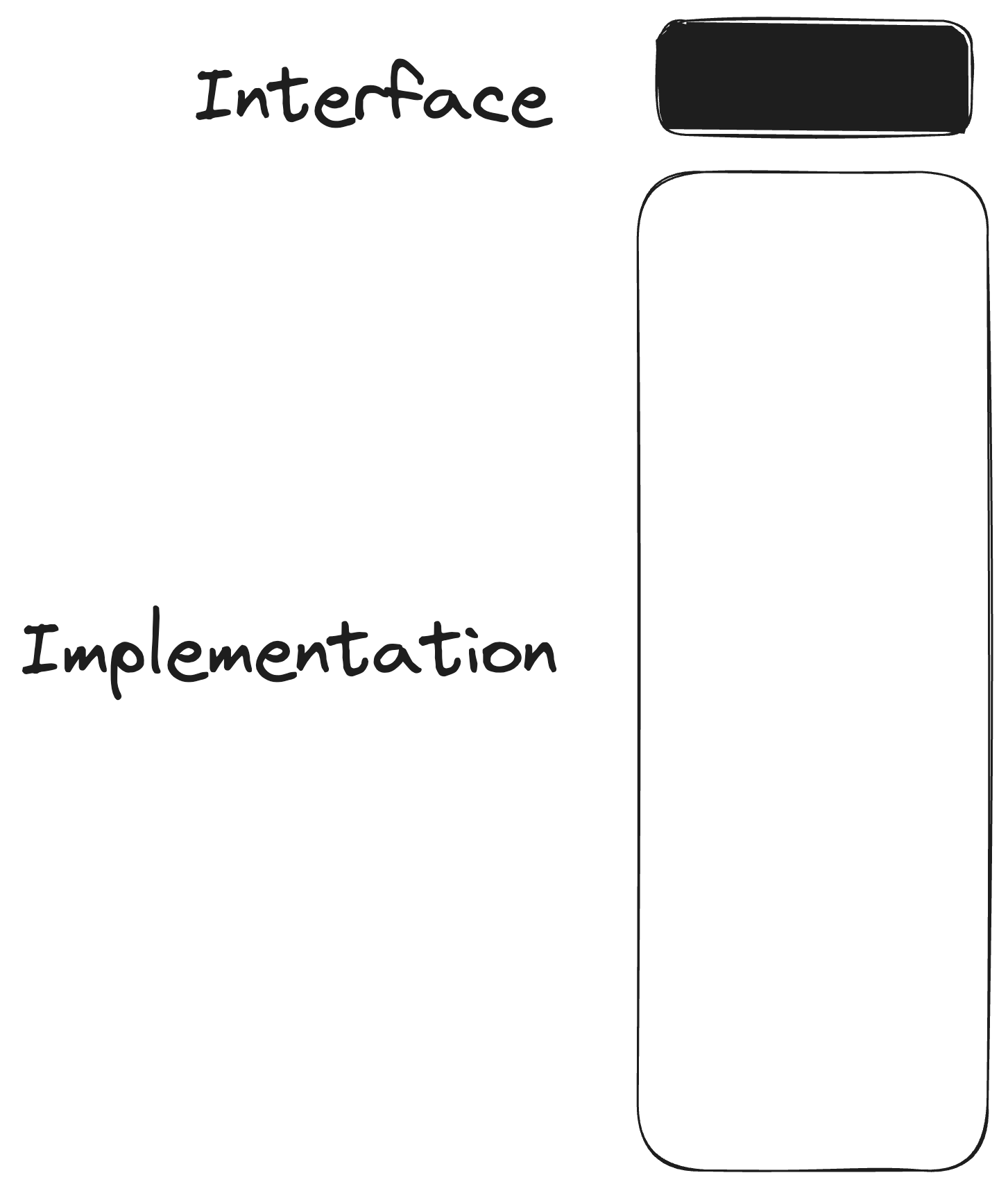

Ousterhout also makes a great deal of a fundamental concept: Modules. Think about anything that can be used to group code and design a modular codebase: “packages”, “components”, “classes”, “libraries”, “services”, etc. Modules help manage Complexity that comes from dependencies between different part of code.

We distinguish shallow and deep modules. Deep modules are “those whose interfaces are much simpler than their implementations” and should be preferred: they hide a big chunk of information and the related Complexity behind a simple interface. The module’s users can then reason from an higher design layer, using high-level Abstractions from the module’s interface without having to know its internals.

A good deep module is for example an AutoComplete UI component that has an interface very similar to a standard input, but it deals with suggestions fetching and options sorting and filtering by itself. It removes the “autocomplete burden” from the developper using it, appart from providing some high-level options via its interface if needed.

Deep modules follow the Unix philosophy: “do one (hard) thing and to it well”. They therefore help to organize the problem space by layers of Abstractions, and pull the Complexity downwards inside their implementations.

That’s a quite challenging task to do, specially when the same people are working across layers. As developers, we need to consistently change posture between being the provider of a module, or its user. This can lead to unfortunate information leakage: “the same knowledge is used in multiple places”, and a trivial change then requires to update multiple different modules.

As Rich Hickey would say: “Design is separating things into things that can be composed”. We separate things by hiding them inside modules.

But in real life?

In reading this book from the perspective of a very Business-driven company, we can quickly think about arguments that will be made against this vision.

With Deep Modules, don’t we risk to over-engineer our code? Not more than with shallow code, the book argues. It’s not because an interface is designed with an high-level, so quite general purpose, Abstraction that its implementation is supporting any potential use case.

Is it really “Agile” to take time for the design of the software? Good question. The book argues that with Agile we are tented to ship features with a “tactical mindset”: as soon as possible without organizing them in a robust design. Should we start by designing everything before coding then? Of course not: “it isn’t possible to visualize a complex system well enough at the outset of a project to determine the best design”.

Instead, we should move incrementally on the problem, like we classically move incrementally on the implementation of a feature. We need to welcome architectural change in the middle of a project (and even maybe throw our first code), add abstractions one after another, and refactor on the go with your design becoming better.

For Ousterhout, an iteration’s output should be Abstractions, not features.

The challenges of Software Design

To conclude, we can only praise the book for being able to highlight very well the challenges of Software Design. There is no absolute method. Any tactic used to the extreme can do more harm than good.

That’s where Software Design is a collective, always ongoing, effort. The Design of a program should be documented by the team responsible for it, discussed and adapted regularly, for example with Defenses of Design documents.

“Working Code Isn’t Enough”, Ousterhout argues. We need to invest into decomposing the problem at hand. This requires time to understand and challenge it properly. The code produced should be strategic, not tactical, and that’s specially true for parts of our software that serve long-lasting features.

But what is “long-lasting”, we may ask? Actually lot of things are long-lasting-enough to benefit for a proper Software Design. It would be a fault to not take the few person-hours that are needed to produce a robust enough design, even for a part of the codebase that is not part of the very few highly critical pieces of code.

That’s the mindset we followed on some projects that were described as temporary set of features by the Business. We nevertheless took the time to understand the problem space, design frontend-oriented endpoints that provided enough high-level Abstractions to iterate with minimal effort on the feature. This has been very valuable in shipping the feature on time, and working on it again after that.

The corollary of Software Design is that some projects will lead to surprising big and costly software changes. That’s expected. By adding new features requirements or new constraints, the problem space of a program can fundamentally change. We have to adapt the program structure deeply for the new features it has to support.

That’s true when following a Software Design mindset, that’s also true without. It’s better to take the time needed for such a refactoring than to hack around and force the code into doing something it’s not designed for. That’s would be the best way to shoot ourselves in the foot by introducing significant technical debt that will soon impact the team negatively.

Let’s also use the book ideas to reason at a bigger scale. Because “Software Architecture and Organization are two side of the same coin”, lot of the insights on managing Software Complexity can be applied to the way we organize ourselves. There is a bridge to be made between “A Philosophy of Software Design”, “Team Topologies” and others ressources like “The Effective Engineer” that use the Complexity prism also (eg. code complexity, system complexity, product complexity, organization complexity).

An effective team communicates much like optimized code: with clarity, modularity, and a focus on simplicity.

Addy Osmani

A Philosophy of Software Design from John Ousterhout is ~190 pages long but a quick read, specially when you go over the examples given quickly and focus on the most relevant insights for your current context. It will be quite an unusual read in the Computer Science section of your library and hopefully give you a new perspective on Software Engineering.

–

This post has originaly been shared internaly at BlaBlaCar. This is a slightly edited version.