How to deal with failure in Redux’s connect… without affecting performances or losing your mind (co-author)

This post was originally published on Medium and written in duo with Victor Graffard.

In a previous article we discussed a common problem when working with React + Redux: how should we deal with failure while connecting a component?

We focused on EitherComponents — components that could either render their children when the data is present in our store or render another component otherwise. After using this pattern heavily for the past few months, we found it sometimes meant writing a lot of boilerplate and dealing with new performance issues.

It was time to try out new things.

This time, Guillaume and I will take you along for the ride. Let’s illustrate our little adventure with a simple application.

This application simply lists some movies and a few actors who starred in them. The catch is that we might not find any actor linked to the current movie…

Back to EitherComponents basics

One of our needs is to fallback on “error” views when we have some missing data while connecting a component to the state. In our example, we would be missing movies entirely or would not find actors tied to a movie.

In order to handle this eventuality we use the classic react-redux connect as follows:

- we retrieve data in

mapDispatchToPropswith a selector that could returnundefined - we use

mergePropsto return either valid props for our real component, or props for our fallback component - we wrap the valid and error components we want to connect with an

EitherComponentHOC that defines which one should be rendered according tomergePropsreturn value

Let’s look at how we typically write such container in our team, using fp-ts:

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable';

import { right, left, map } from 'fp-ts/lib/Either';

// EitherComponent - Setup

const FallbackComponent = () => null;

const EitherMovie = eitherComponent(FallbackComponent, Movie);

// Connect

const mapStateToProps = (state, { id }) => {

// Movie or undefined

const movie = movieFromId(id)(state);

if (!movie) {

return left(() => new Error('missing movie'));

}

const actors = actorsFromMovieId(movie.id)(state);

return right({

movie,

actors,

});

}

// Either valid or "error" props

const mergeProps = (

maybeStateProps,

{ upvoteMovie, downvoteMovie },

{ id }

) => {

const eitherProps = pipe(

maybeStateProps,

mapLeft((err) => {

console.error(err);

}),

map(({ movie, actors }) => ({

movie,

actors,

upvoteMovie: () => {

upvoteMovie(id);

},

downvoteMovie: () => {

downvoteMovie(id);

},

})

);

return { eitherProps };

};

Two problems here. First, that is a hefty +40 lines of boilerplate code in production. Reading it is not straightforward. Second, mapStateToProps returns an fp-ts Either value (new reference for every left or right call) so redux will re-render the component every time the state changes. That is a performance issue.

We decided to give react-redux’s hooks useSelector and useDispatch a try, producing the cleaner, shorter and simpler code below. Let’s see how.

import { useSelector, useDispatch } from 'react-redux';

const movieWithActors = (id) => (state) => {

const movie = movieFromId(id)(state);

if (!movie) {

return { error: new Error('Missing movie') };

}

const actors = actorsFromMovieId(id)(state);

if (!actors) {

return { error: new Error(‘Missing actors’)};

}

return { movie, actors };

}

const MovieContainer = ({ id }) => {

const dispatch = useDispatch();

const {

error,

movie,

actors,

} = useSelector(movieWithActors(id));

const upvoteMovie = () => dispatch(upvoteMovie(id));

const downvoteMovie = () => dispatch(downvoteMovie(id));

if (error) {

console.error(error);

return null;

}

return (

<Movie

movie={movie}

actors={actors}

upvoteMovie={upvoteMovie}

downvoteMovie={downvoteMovie}

/>

);

}

What is the problem with connect and EitherComponents?

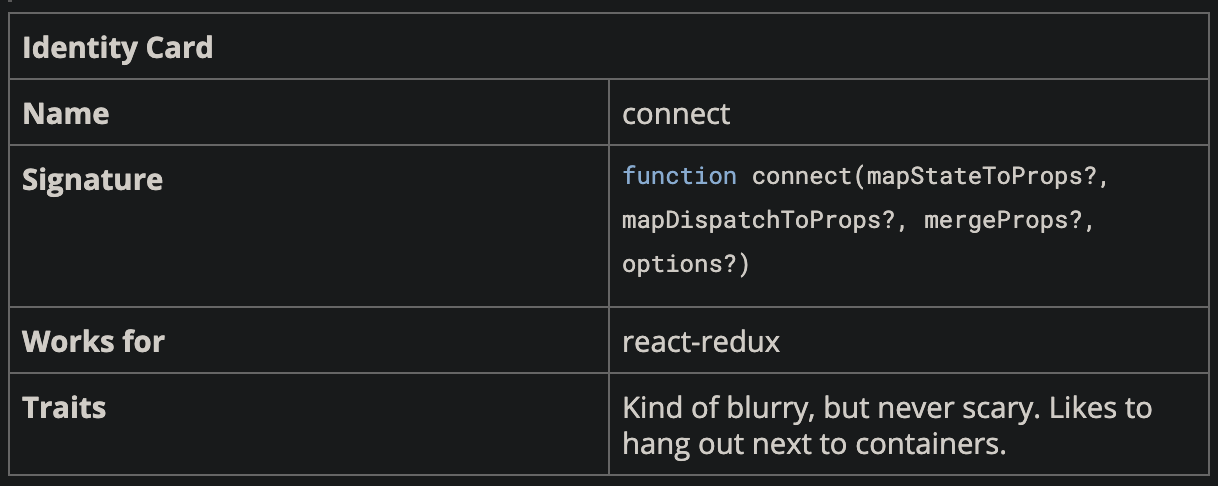

Let’s take a closer look at react-redux’s connect.

connect can take three parameters:

mapStateToProps: receives state and optionally the container’s props — it is used to retrieve data from your store and map them to your component props.mapDispatchToProps: can be either an object or a function receiving dispatch as parameter — it is used to map actions you can then dispatch from your component.mergeProps(optional): receives yourmapStateToProps+mapDispatchToPropsreturn values, and the container’s props — it is used to craft the component’s final props. If not provided,react-reduxsimply spreads state props and dispatch props to the component.

Three functions to write for each Container

We found that using EitherComponents often meant writing complex mapDispatchToProps and mergeProps functions when in need of several stored datas. In fact, the boilerplate itself already represents more than 40 lines.

If a new developer joins your project and is not comfortable with Functional Programming or EitherComponents, they might not understand why there is so much code for such an easy mission: connect a component to the store.

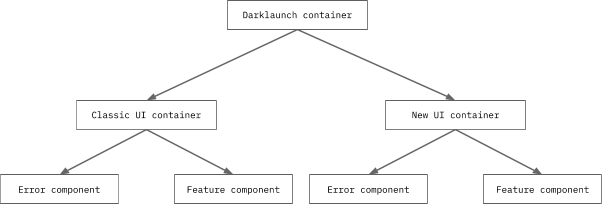

Container in Container in Container…

This pattern is hard to scale. We use darklaunch and features flags a lot to deploy new UIs. EitherComponents are a part of that method: a selector tests the value of a flag for the current user and we use mergeProps to decide whether to render the classic UI or the new one. Doing so, we usually end up with this tree of containers:

That is a lot of containers to render a simple feature.

How does connect handles these props refresh?

The last problem we are facing is the difficulty to write mapStateToProps without creating excessive renders.

Redux runs a shallow comparison on your mapStateToProps returned object every time the state changes. If one of the values contained in the returned object changes, the connected component will get rendered again.

We found it is really easy to provide connect with a function that creates new references every time, ending up rendering the children at every state change.

function mapStateToProps(state, { id }) {

const actors = getActorsFromMovieId(id)(state) || {};

const movie = getCurrentMovie(state);

return {

movie,

actors: {

...defaultActors,

...actors,

}

}

The actors value here will be a new reference every time the function is called because writing { ...defaultActors, ...actors } means creating a new object — and thus a new reference — containing the content of defaultActors and actors.

These pitfalls may not be easy to spot. Here is another example when using fp-ts:

function mapStateToProps(state, { id }) {

const alwaysHereData = niceSelector(state);

const actors = getActorsFromMovieId(id)(state);

return {

...alwaysHereData,

// using fp-ts Option helper to create None if movie's id is undefined or

// Some<Actor[]> if present

actors: fromNullable(actors)

};

}

Once again, actors will be a new reference for every call because fromNullable from fp-ts returns a new object every time it is called.

To sum it up, here is our list of identified EitherComponents drawbacks: they are boilerplate-heavy, they are hard to scale and they can be a burden on performance.

Now let’s dive deeper into our alternative: react-redux’s hooks.

An alternative: react-redux’s hooks

react-redux now exposes these React hooks:

useSelector— applies a selector over the state, re-renders the component if the returned ref changed (does not default on a shallow-compare). You can provide an equality function as the second parameter (react-reduxexports the shallowEqual) to change the strict equality behaviour.useDispatch— returns a dispatch function in order to set up your actions.

Like all hooks, be sure to call them at the top level and not inside loops, conditions, or nested functions.

With these two, a classic connect could be re-written as follows:

function ConnectedComponent({ id }) {

const dataFromState = useSelector(dataSelector);

const dispatch = useDispatch();

const onAction = () => dispatch(actionCreator);

return <DumbComponent data={dataFromState} onAction={onAction} />;

}

Replacing EitherComponent with useSelector and useDispatch

Our need is a little bit more complex than the example above. Our container should:

- allow multiple variations (at least 3: error, darklaunched UI, classic UI)

- work for complex state selection (selector B that needs selector A’s output)

- be efficient (only re-render the component when needed)

It’s easy to do the simple error/no error variation:

function Container({ id }) {

// Movie or undefined

const movie = useSelector(getMovieFromId(id));

if (!movie) {

return <ErrorScreen />

}

return <Movie movie={movie} />;

}

Using a memoized selector here, we are sure this will re-render only when the selector returns a new movie object.

How about dark launching new UI?

function Container({ id }) {

// Movie or undefined

const movie = useSelector(getMovieFromId(id));

// true/false

const newUIBeta = useSelector(isNewUIBetaActivated);

if (!movie) {

return <ErrorScreen />

}

if (!newUIBeta) { // old

return <Movie movie={movie} />;

}

// new

return <NewMovie movie={movie} />;

}

Clean and simple.

How about a complex selection scenario: what if the isNewUIBetaActivated selector above depended on a Movie attribute?

We cannot call useSelector for the Movie, fallback if nothing is returned, then call useSelector for the darklaunch value because that would break the rule of Hooks : they must be called at the top level.

function Container({ id }) {

// Movie or undefined

const movie = useSelector(getMovieFromId(id));

// Not yet! This should come after the useSelector below

if (!movie) {

return <ErrorScreen />

}

// true/false

const newUIBeta = useSelector(

isNewUIBetaActivated(movie.type)

);

if (!movie) {

return <ErrorScreen />

}

if (!newUIBeta) { // old

return <Movie movie={movie} />;

}

// new

return <NewMovie movie={movie} />;;

}

Our solution is to craft a single useSelector that is able to retrieve the two different parts of the store:

function getDarklaunchAndMovie(movieId) {

return state => {

const movie = getMovieFromId(movieId)(state);

if (!movie) {

return { error: true };

}

const newUIBeta = useSelector(

isNewUIBetaActivated(movie.type)

);

return {

error: false,

newUIBeta,

movie

};

}

}

function Container({ id }) {

const {

// true/false

error,

// true/false

newUIBeta,

// Movie

movie,

} = useSelector(

getDarklaunchAndMovie(id),

// don’t forget the shallow comparison as we are using an

// object composing selector results

shallowEqual

);

if (!error) {

return <ErrorScreen />

}

if (!newUIBeta) { // old

return <Movie movie={movie} />;

}

// new

return <NewMovie movie={movie} />;

}

And voilà! We now have our 3 variations built on inter-dependent selectors and performances are kept in check.

getDarklaunchAndMovie really looks like a mapStateToProps here, but thanks to the hooks declarative syntax the container code is way easier to understand than what we had with EitherComponents before.

You can find here the source code of an extended example around the Movie list application. It highlights other use cases for this pattern using Typescript, functional programming with fp-ts, reselect, EitherComponents (on this commit) and react-redux’s hooks.

Conclusion

Having one react-redux container rendering different things depending on what is found in the store (data, missing data, darklaunch variations, etc.) is still immensely useful.

Our first implementation relied on the use of react-redux’s connect and a special EitherComponent HOC, but it made developers write a lot of boilerplate and hard to read code. It leads to a number of mapStateToProps being written the wrong way, making the component re-render at every state change.

With the use of react-redux’s hooks, we still separate containers from “dumb” components, but with fewer code, therefore fewer opportunities for bugs and performance issues. It made the code easier to read and more flexible, allowing us to handle more than 2 variations in a single container.

It is our definitive solution to this issue … until next time!

A big thanks to our lovely colleagues who took time to help us write this article: Axel Cateland and Benoit Rajalu!